Bulletin Board 41

Heritage diver watches, our new style survey and catching up with The Sartorialist.

We’ve got a bunch of cool stuff this week including a wrist check with my friend John Sugden, the debut of our new style survey and a long catch-up with Scott Schuman, aka The Sartorialist. But first, a heads up that I’ll be at Alfargo’s Marketplace in NYC this Friday and Saturday selling wares from my own closet alongside a lot of other great vintage vendors and resellers. If you’re in town, come check it out.

WRIST CHECK

THE WATCH: A 1960's Blancpain Aqua Lung.

ITS OWNER: John Sugden, owner of traditional Highland outfitter Campbell’s of Beauly.

THE STORY: I've been into watches ever since I was given an Omega Seamaster mid-size for my 21st birthday. When I got it in 2001, I went to the store and chose it, preferring it over the larger 41mm version. I have always preferred to be understated, and found the larger watches far too bulky and showy. To this day, nearly all my watches are 38mm or less. When my grandfather died, my grandmother gave me his 1953 Universal Geneve Tri-Compax. This is a beautiful dress watch, and it really got me hooked on watches aesthetically as it is a really stunning timepiece. It's amazing how many people notice it, despite it not being as valuable as many sports watches these days. Again, it's a smaller watch at 36mm, but is incredibly elegant, timeless, and also understated. These are the three prerequisites I have when looking for a watch.

I wear the Tri-Compax sparingly because it is also a delicate watch, and of huge sentimental value. Having followed the vintage watch trend, I do like the look of many sports watches, particularly the Rolex Submariner, though I've always felt I'm not a Rolex person. However, model aside, there are a lot of them about, and I prefer things that are rarer. I also felt that 40mm was too big, and so I started to look into other dive watches. There are some really interesting alternative options when you look about, starting with say Wittnauer's Skin Diver at the cheaper end of the scale. However, I settled on Blancpain, as they were the first company to build a modern dive watch in 1953 with the Fifty Fathoms. It was way outside my price bracket, but also too big at 42mm, and I felt the bezel and insert were also too big for the size of the dial. I didn't feel the balance was right.

While scrolling through Google images of the Fifty Fathoms I came across the Aqua Lung and loved it immediately, and from there the research started. Part of the Bathyscape range at the time, the Aqua Lung was a more affordable interpretation of the Fifty Fathoms, which suited me as it fit into my budget, as well as being, I felt, a better looking and more balanced watch than its older brother. It took me about two to three years to find a really nice example, which came up for sale at Bonhams in NYC. The rest is history, and it's now my daily wearer, a heritage diver with an understated charm.

DRESS CODE

We’re shaking up our Uniform column a bit because we found ourselves wanting to know more about our subjects. We're calling it Dress Code--it’s a bit more personal, more biographical, and all-around interesting in the best scattershot-way. .

Our first subject is Darryl Lesure, whom many readers might recall as the cover star of Wm Brown #14 back in Summer 2023. A Detroiter by birth and an Atlantan by choice, Lesure spent nearly three decades in corporate hospitality before striking out on his own as an image consultant with his business That Part Styling. He’s since become a fixture at Pitti, where his shock of white hair, idiosyncratic eyewear and million-dollar smile have allowed him to stand out even amid the peacocking throngs. Few guys in menswear look as if they’re consistently having as much fun as Lesure, so we asked him to give our questionnaire a go. —Eric Twardzik.

How early do you remember being interested in clothing—and how?

My interest in clothes started around middle school, so about 12 or 13 years of age. Church attendance required a higher and more formal level dress code on Sunday.

How would you describe your personal style in two words?

Traditionally relevant.

If you have a uniform, what does it look like?

Sport Jacket, khakis or year-round wool pants, suede shoes, plain blue or white oxford shirt (unbuttoned points).

Who was your style icon when you were young?

Sidney Poitier.

Who is your style icon now?

Kamau Hosten and probably… "Me.”

How often do you edit your closet, and how?

I add more than I purge and unfortunately that could be monthly but I edit according to the seasons.

What's in your travel kit?

Toothpaste, deodorant, clear eyes, face cream, sun screen, cologne, hair cream, twist up comb, coconut oil, and beard oil.

Is there an article of clothing you got rid off—but wish you'd kept?

My light gray leather boot cut trousers. Silly me.

What would you never, ever part with?

My brown Edward Green Galway boots.

What style rule is worth breaking?

I live in Atlanta, and white jeans only in the summer used to be standard. I broke that rule many years ago!!!

Which isn't?

Black tie is black tie. Black tie is a black tux! Black tie is black socks!

If you had to buy from a single designer/brand for life, it would be...

What independent designer/store deserves more attention?

I reserve the right to keep silent. But… I can be coerced via text or DM by your readers!

What style advice would you give your younger self now?

Buy the best you can afford one time and wear it to last.

THE SARTORIALIST

Before Substack, before Instagram, and even before Twitter, there was The Sartorialist. Founded in 2005, the blog simply posted photos of real people in their real clothes, long before algorithms and hashtags made anyone with a smartphone a model-in-waiting (or worse, an influencer).

The man behind it all was Scott Schuman, who can rightly be considered the father of the street style-photography that rules the internet today. 20 years after the blog that started it all, Schuman has joined the brave new world of Substack with The SartoriaLIST, a joint venture with his girlfriend Anastasia Novaia, which covers both men’s and women’s style in bi-weekly posts. I recently caught up with Schuman from his current home in Milan.—ET

What’s your origin story?

So, I grew up in the fashion capital of Indianapolis, Indiana. And it was way before the internet, and I played sports. I was a typical American kid playing baseball and basketball and football and all that stuff. But all the athletes that I read about were always talking about GQ magazine and what they were spending their money on. And I somehow became more interested in that than the sports themselves. And so I started buying GQ in eighth grade. For a kid from Indiana, that really was a window to the world. I didn't understand what this world was because it didn't look like where I lived. There were older people looking like they were having a lot of fun.

I didn't see any older people having fun where I lived. They were all working, doing whatever they had to do, but this looked like a fun life, whatever that life was, in New York and these different places. And it was at that time when Armani and Italian fashion was more important than Paris. I think it was definitely more directional, and it was leading the pack. And he had a great photographer named Aldo Fallai, who was kind of like, I wouldn't say the Italian version of Bruce Weber, because it wasn't as sexy as Bruce Weber.

Armani at that time was like Ralph Lauren, but with an Italian tint to it. There were a lot of family shots and beautiful men, beautiful women—Italians—so it was really equal to what Ralph Lauren was doing at the time. And to me, that world just seemed so magical because I could kind of recognize it. I understood, OK, that's a family. But I didn't understand these incredible villas they lived in and this romantic, beautiful lifestyle they were projecting. And I've been chasing that, I think, ever since. I don't know because I've never done any drugs, but from what I hear, once you do that first line, it's something you're chasing forever.

And because it was so hard to access and find anything about it. It felt even more elusive, more exciting. And so it just kind of grew from there. I at some point realized fashion is what I wanted to do, but I had no idea how I would do it. I didn't know anybody in the fashion world. And I took a chance. I studied costume design at Indiana University, and then went to New York, But I was not, at that time, confident in my ability to do design, and so I did sales and did that for about 10 years. But after a while, especially when I had my kids, I picked up a camera and started taking pictures and got in touch with what my creativity was. I never knew what my creativity was. And I eventually found it with photography.

And at some point after 9/11, after having a showroom and being in fashion for a long time in sales, my nanny who watched over my two young daughters went back to Honduras, and I watched the kids. I took pictures of them with this little point-and-shoot camera and it really unlocked something. I liked photography, but I had never found anything I wanted to shoot until I had my kids.

And then I found that link, that missing creativity, that thing of, “Okay, shoot what you love.” I don't have to shoot mountains, I don't have to shoot architecture, I should just shoot the things I love. I started shooting on the street, both men's and women's wear, and what I found interesting in fashion. I had been in it long enough and by that time I felt very confident in my point of view. And it just took off overnight.

It was at the very beginning of internet culture and social media—the blog period. There was really nothing fashion-driven on the Internet—Vogue.com was not even a thing—it was called Style.com at that time—and it wasn't considered important. They weren't running editorials from the magazine—just runway photographs. Within months of starting The Sartorialist, they called and asked me to start shooting—at first it was just Milan, then men’s fashion week. I was very aggressive—I knew this was my moment. I had finally found my thing. Even when I was in Milan on that first trip, I kept saying, “I can do Paris, I can do it.”

They extended my trip on that very first trip and I shot Paris. And then the next season, which was in June 2006. By September, I convinced them to let me do women's because my that was my background. After that I started doing Pitti in January 2007. In the beginning, it was me and Bill Cunningham at the the New York shows, but he never went to Milan, and because of the internet, people all around the world were seeing it and being inspired. Pretty quickly, it went from nobody to a ton of people at the shows and at Pitti Uomo, and the story kind of wrote itself.

Over the years, how did The Sartorialist itself change?

Well, for me, it stayed very much the same. I went to fashion week, but I also shot on the street every day. The things that changed were more from the outside. There were more people trying to do what I do. There were a lot more people at the shows. There was a lot more competition. People went from becoming bloggers to influencers. So my work didn't change so much, but what was happening around me changed a lot.

The big change during that period was going from blog to Instagram because the blog was still a little bit heavy: too much work for most people to do themselves, but Instagram was so easy. The people I used to shoot—the only images the world saw of these people were photographs that I posted.

Then when Instagram came along, and everyone started taking pictures of themselves with their iPhones, a bit of the romance was lost. The photographs were never as good, and the important mystery of the images was lost in the process. This really was the biggest departure from the days of the blog, when it was more curated, and fewer people were producing individual content. This definitely changed with Instagram, and it wasn’t necessarily a good thing. People get addicted to the likes and response, and they want to please their audience. And so they just post things, I guess, to keep in touch with the small audience that they're growing, but it doesn't create the romance and all of that. And so that's really the biggest change. During the blog days, it was more curated, and, I think a little more beautiful. Now it's more facts as opposed to dreams.

Do you see The SartoriaLIST as a way to counter that?

In the blog days, I did a lot more writing. It was more comfortable—set up for writing. When Instagram came along it was very visual, which I loved, but it’s not really a platform that’s about writing.

During Covid, I did a menswear book where I wrote a lot and that really killed me. I was kind of burned out after that, but lately, I’ve been wanting to give more context to my images. I shoot and post pretty quickly, pretty chronologically, but sometimes you need some time to look at what you're seeing and see trends developing or things that are interesting to you.

Maybe an image that I saw in Florence during Pitti, I want to pair with an image I saw in Paris, because I’m seeing tweed coats or plaid coats or something. Substack really makes it much easier to put that together, to review, and write a little bit more—it reminds me of the old blog days. Also, I have a very wonderful girlfriend, Anastasia, who I've known now for 14 years, who I’m collaborating with on it. I've always thought she had super great style and a great take on fashion. To have her personifying the women's point of view is great, because I can photograph her and she can write about women's. I can't think of any other Substack that talks about fashion from both a man and a woman's point of view, where she can talk about what she likes, about what she sees in menswear, I can talk about what I see in women's. I think it's really unique, because most of the time it's guys talking to guys, or girls talking to girls, and this one is a bit of both.

I hear you have an Armani archive?

Yeah, like I actually have a secret Instagram called Armani Archive that I started doing during Covid. Armani was my hero growing up, the way for some people, Michael Jordan, or Tiger Woods is their hero. Not only for the design, but the way he talked about design, who he was, his personal style, and the images that he created with Aldo Fallai. And for someone who was young and into fashion, he was the one who I related to the most. More than Ralph Lauren, who is great, but his thing was about a kind of luxury elite, not elitist, but a very wealthy kind of lifestyle that I just never thought I would have. Armani was much more about design—he talked about fabrics, he talked about shape and cuts, and everyone can relate to that. Even if you don't have a lot of money, you can still care about fabrics and cut and shape.And when I looked at pictures of Armani, he kind of reminded me of my dad.

He wasn't as flamboyant as what designers were thought of at that time. He was more serious. It was an art, the way any other artist would talk about their work. He was super cool. And it was a growing small business at that time, and it was very cutting edge. People now think of Armani as being so classic. They don't realize how cutting edge he was from 1981 to 1990. He was as cutting edge as what Prada is today, or any designer you think of. And what was unique for him is that he was just as directional for men's and for women's. And then the whole Hollywood thing. I don't find that part particularly interesting, but a lot of people related to that.

He was kind of my North Star. And I started collecting things, things I still have now. A funny story was that when I was in high school there was one store in the center of Indianapolis called L.S. Ayres that sold Armani, the white label Armani, not the Italian higher-end label. And so I begged my parents. There were 3 shirts that were on sale. I really wanted them for Christmas, and the salesperson took pity on me. I picked out my size and he held them back for me. And they went and bought them. And I loved them so much I didn’t take them out of the packaging for about three months. I just looked at them. I was probably in ninth or tenth grade, something like that, and I just would sit there and look at my beautiful shirts. And I think that in the back of my second book, my portrait is a shot I took around that time, wearing one of those shirts. I can still wear those shirts.

I have a book coming out, I think this September—we're still coming out with the exact date. It's a book about Milan that Taschen is printing and Armani wrote the foreword for it. I was really excited to have him do that because he's a big part of why I moved here, once my kids are grown up and out of school and all that. And so I'm now having a chance to really live the life I always dreamed about.

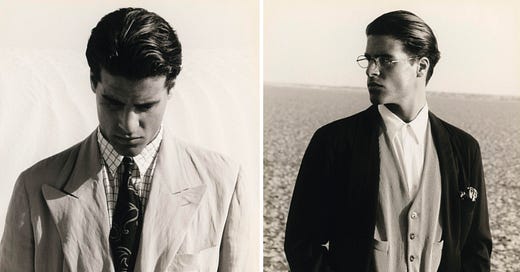

That ‘80s, 90s ‘Armani palette and styling seems to be coming back for men. What do you think is the reason for that?

It's absolutely time. The thing that's happening with men's fashion now, and it's really unusual, I think it's the first time this has ever happened, but you had Armani in the ‘80s with what we used to call a drape suit. It was looser, more fluid fabrics. Then you went on to the Hedi Slimane, the much slimmer suit. Then you had a shrunken suit with Thom Browne. And now we are ready for something new but there’s not really a leader of that revolution the way that Hedi Slimane or Thom Browne or Armani was at that time.

And it seems like the customer is ready, the fashion guy is ready for a looser, cooler silhouette. But nobody has really embodied that. Nobody's led the way. So I think people are looking back and saying, Ok, we want something like this. Who did it the best? And Armani obviously did it the best.You know, people think of Armani as kind of oversized. But when you really look at Armani in the strongest period from ‘84 to ‘90, not only were the silhouettes great, super soft fabrics, soft collar shirts, but the colorations were great. The way he would mix a striped shirt and a dotted tie with a plaid suit with a slightly extended shoulder. Double pleated pants that were higher in the waist, always with white socks. When you look at his ads, he himself had a lot of little style quirks, almost like Agnelli. Armani always had this kind of loose silver watch on his wrist. He would wear white socks with brown suede shoes and soft collar shirts. So there were a lot of little things I think people want again. Obviously we’re moving to a looser silhouette and I really hope somebody takes the ball and runs with it. Whoever ends up doing it will, I think, be the leader of the next revolution.

Love the vintage 80s Armani photos featured in the Scott Schuman interview. Do you know of any bespoke or MTM tailors who would specialize in that style of suit? US-based preferably but doesn't have to be.